A semantic search for artworks

Stefan van der Weide & Sjors Lockhorst | 2024-12-13Introducing artexplorer.ai

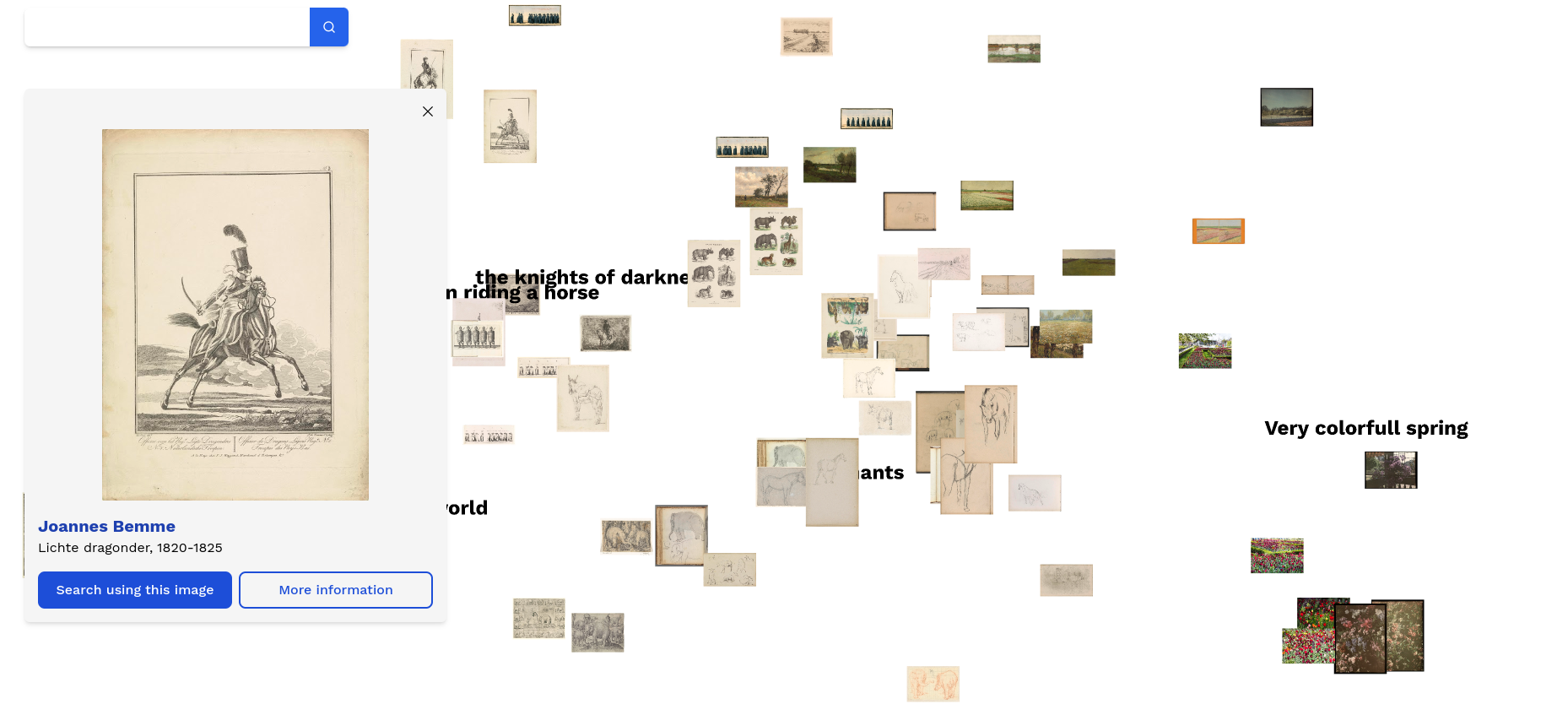

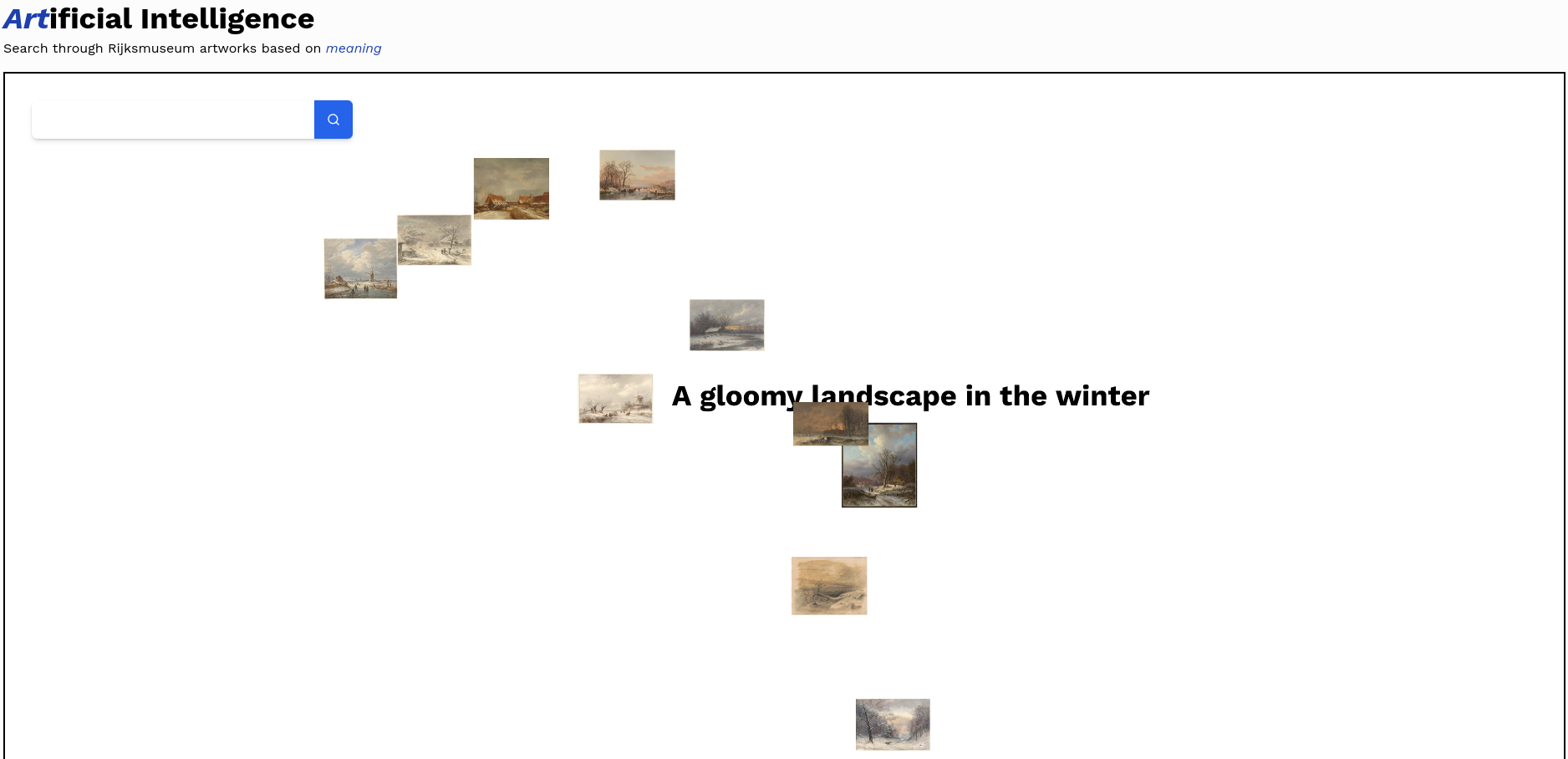

A search engine that lets you search through artworks based on a 'vibe', aka the meaning or semantics of a text. Try it out by going to artexplorer.ai, and searching for a vibe. For example:

'A gloomy landscape in the winter'

This will give these results:

You can then click images to learn more about them, and find more similar images like them. Images will keep on being added to your screen, until you refresh, which clears the page and lets you start over again.

Currently, it supports all public artworks from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, with the ambition to add collections from other open sources at a later moment.

Background

Imagine this, you just finished your visit to the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum and you want to tell your friends about this amazing piece of art that you saw. It was this beautiful painting of a group of people in a bar, having a great time. However, you don't remember the title... Now what?

You could go to this website which shows you a random artwork from their collection, but that gives you about a 1/500.000 chance each time you request a new artwork. Not ideal. You also can go to Rijksstudio and see if you can find the paiting by keyword or even color, but what if that doesn't work? Wouldn't it be great if you could just normal language, much like asking ChatGPT a question, to find what you are looking for? That is exactly what we thought!

Side note:

It turns out the Rijksmuseum had a pretty similar idea to ours. Their take is a little different, though. They ask you a specific question and get artworks that matches your answer.One thing their version doesn't have though is our search by image feature. Still, their tool is super fun and worth checking out!

How does it work? 🧰

TLDR

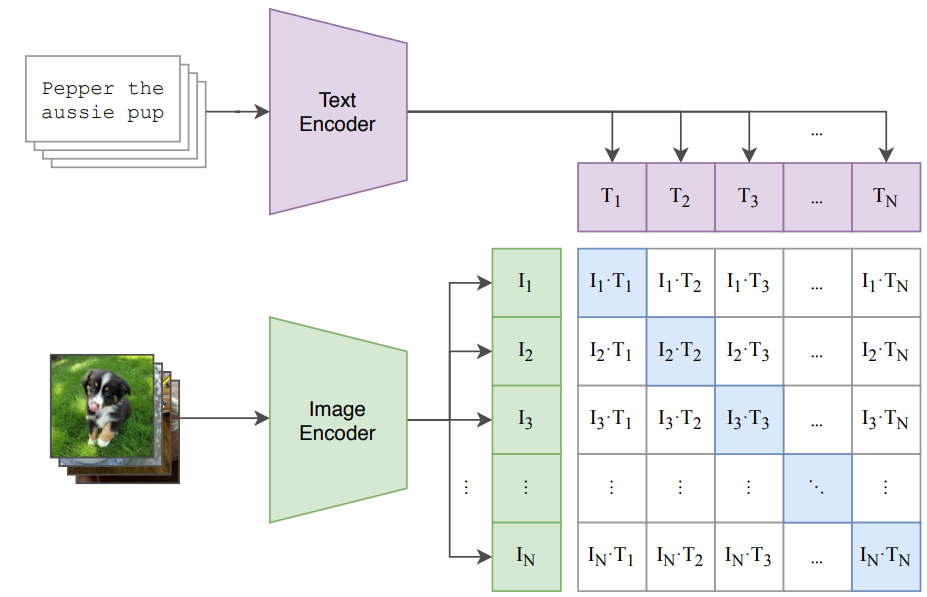

The art search leverages OpenAI's multi-modal vision and language model CLIP to embed images and texts in a shared embedding space. We scrape the Rijksmuseum API, embed all images with the CLIPVisionModel and store them in Postgres using pgvector. When a user enters a text query, we embed their query using CLIPTextModel.

Image taken from CLIP paper

Image taken from CLIP paper

We use this text query embedding to search for the top-k nearest neighbours in our pgvector database. Before sending the response, we use PCA to project down the CLIP embeddings from 512 dimensions to 2 dimensions (x, y) for visualization of the embedding space.

The frontend displays the retrieved artworks in their respective places. The user can now also do image-to-image search with any of the retrieved artworks. You can find the source code here. Keep reading if you want to learn about the details!

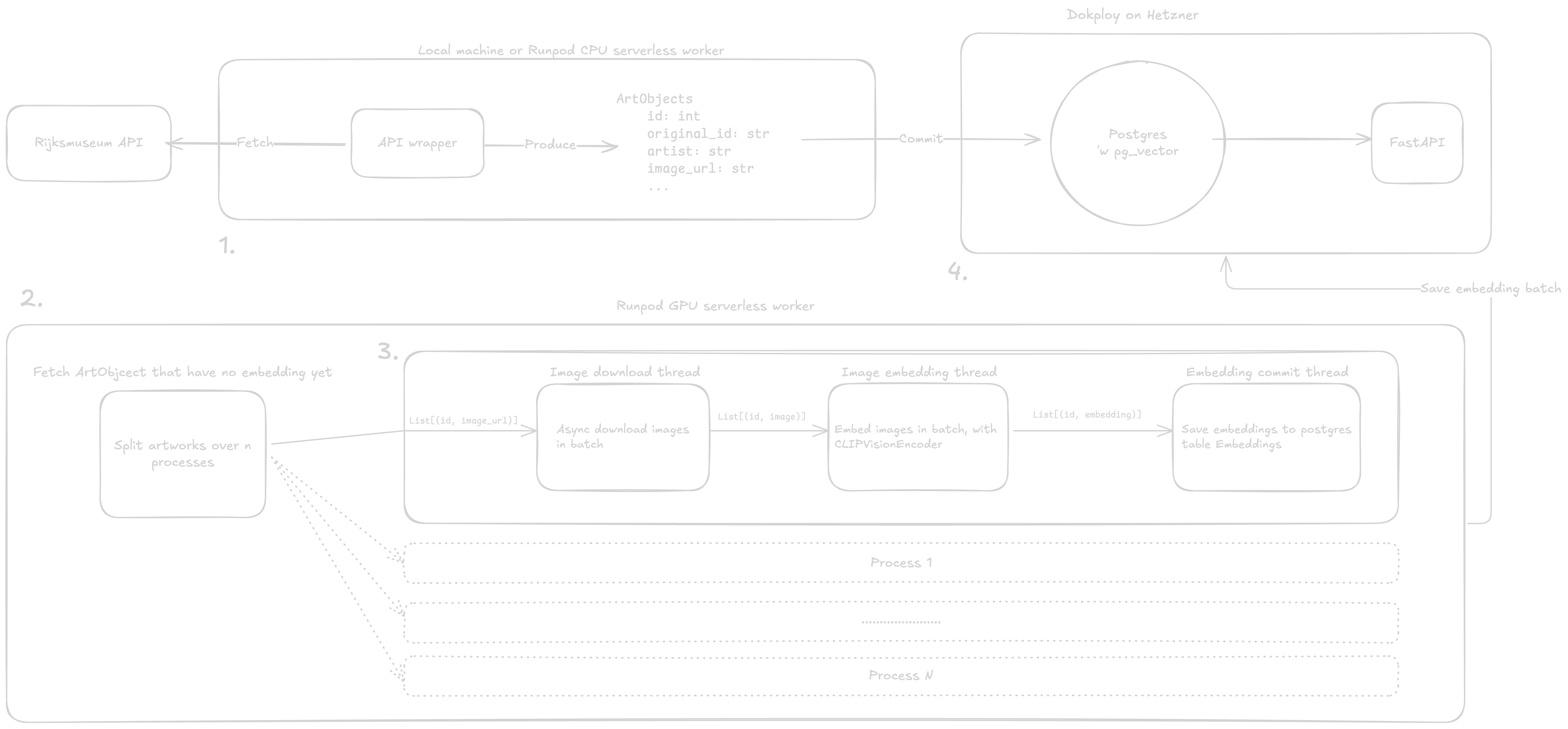

ETL pipeline 🏗️

Drawing of the ETL pipeline, click to enlarge

1. API Scraping 🕷️

To work with the vast collection of the Rijksmuseum programmatically, we built a pipeline to extract metadata for all available images. Here’s a breakdown of the options we explored and how we landed on the optimal solution.

Initial Approach: Historical Data Dumps

Our first thought was to use the Rijksmuseum's Historical Data Dumps. These dumps contain metadata for all objects in their collection, which seemed promising at first. However, the most recent data dump available was from 2020. While this would work for many use cases, we wanted the freshest data possible. So, the search continued.

Exploring the Collection JSON API

Next, we considered their Collection JSON API, accessible via /api/{culture}/collection. This endpoint allows fetching metadata in a convenient JSON format. However, there’s a catch: the API paginates results and imposes a limit of 10,000 records. To retrieve the entire collection, we’d need to split it into chunks of 10,000 or fewer records (by artist, decade, or other attributes). Since there was no straightforward way to achieve this (believe us, we tried), we kept this as a fallback option.

The Jackpot: OAI-PMH API

Finally, we found the OAI-PMH API (Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting). With metadata harvesting in the name, it was clear this was designed for our exact needs. This API delivers metadata in various XML formats. After querying the GET /oai/[api-key]?verb=ListMetadataFormats endpoint and testing all the available formats, we settled on oai_WPCM because it contained all the attributes we needed (e.g., image URL, artist name).

Handling Pagination with resumptionToken

To extract the data, we had to manage the resumptionToken mechanism. The API returns a batch of artworks (e.g., 25) along with a resumptionToken. This token is required for subsequent requests to fetch the next batch. Unfortunately, this sequential approach meant we couldn’t easily parallelize the requests to speed up the process. Instead, we kept things simple and wrote a script that repeatedly fetches artworks as long as the resumptionToken is provided.

Future-Proofing the Code

This implementation is tailored specifically for the Rijksmuseum API. However, we designed our codebase to handle additional sources in the future with minimal changes.

2. Image processing 🖼️ → 🤖 → 📊

Now that we have all metadata of the images we want to embed, we need to do four things.

- Fetch all metadata of artworks without embedding, divide them over n processes.

Then each process:

- Downloads the images,

- embeds them using CLIP,

- stores the embeddings in pgvector

Each of these steps runs its own thread.

Fetching artworks without embeddings 🖼️

Once we start the embedding phase, we do a simple SQL query, where we fetch all artworks that have no embedding yet. Then we divide these artworks over the total amount of processes n. We spawn n processes each with their own artworks to embed.

Downloading the images ⬇️

Since we have quite a reasonable scale of ~560.000 images, we prefer this to be fast. Luckily all images are served via a Google CDN, which is blazingly fast as is. We considered downloading and saving images to an object storage like S3, but we figured that fetching the images from Google CDN directly is simpler. Additionally, the Google CDN allows you to control the resolution of the image by a query parameter.

Consider the following example URL:

https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-ZYQ7IcfJ45yQOPnmhzBkZK2mc2F_e7bUMDgKaY-miSl0f8y3o-Q--H3R81q-2q1cfqFqoDlDgyLDW3OHJqin_ugnB_KRIfZaV-9xX2Y=s0

Notice how URL ends with =s0. This means the image is returned in full original resolution.

We can change this parameter to control the resolution of the image. If we pass

=w400 instead, it will fetch the image rescaled to have width 400 pixels, while keeping the correct aspect ratio:

This was very helpful, since we probably need a lower resolution for embedding, than we do for finally displaying the artworks in the frontend.

For embedding, we settled on a resolution of

w1000.

Downloading of the images runs in its own thread. This is done so the downloading of images doesn't block the embedding of images, or saving of embeddings to database.

The thread is essentially a consumer of list[tuple[id, image_url]] and a producer of list[tuple[id, image]]. There's no need to persist images to disk, so images always remain in-memory.

We fetch images async in batches of a configurable retrieval_batch_size, and put these images in a queue.

3. Embedding the images 🤖

Embedding of the images is done by a thread that consumes items from the queue which is being filled by the image download thread.

This thread thus consumes list[tuple[id, image]] and produces list[tuple[id, embedding]] by using CLIP.

This is again done in batches, which is configurable by embedding_batch_size.

This thread will thus wait untill at least embedding_batch_size id image pairs are in the queue, and then start embedding the images.

The results are put in another queue, which is read by the tread that commits the results to the database.

4. Store embeddings in vector database 🗄️

This thread simply reads each of embeddings batch from the previous queue, and commits them to the pgvector database.

Backend 🖥️

The backend is based on FastAPI. It has the CLIP text model loaded in memory and embeds incoming text queries on CPU. Since it's a relatively light load, no GPU is needed for this. Other than that the API is pretty simple, wich was our goal. The API needed to get out of our way so that we could focus on the ETL pipeline. There are 3 GET routes:

/queryThis endpoint takes a query entered by a user on the frontend, embeds it and finds the best match in our database/imageThis one is a bit more interesting! It takes the index of an image that is currently displayed on the frontend, such as321, and find images that are closely related to the image corresponding to the index. This is how we facilitate the "search using this image" functionatlity./healthThis is a bog-standard endpoint that only returns the string"ok"and a200status code. It's used during development and is useful if you quickly need to check if the API is still up and running.

Check out the backend docs for the openAPI spec if you want more details.

Vector search using pgvector + SQLModel

We used the pgvector extension for PostgreSQL to store and index vectors in regular tables. Then we use the amazing Python package pgvector-python, providing us with a field we could directly use with SQLModel.

from pgvector.sqlalchemy import Vector

from sqlalchemy import Column

from sqlmodel import Field, SQLModel

class Embeddings(SQLModel, table=True):

id: int | None = Field(default=None, primary_key=True)

image: Any = Field(sa_column=Column(Vector(512)))

art_object_id: int = Field(foreign_key="artobjects.id", unique=True)

Then once we have obtained some vector, to which we want to find a the top-k closest neighbors, we can simply do:

from sqlmodel import Session, select

top_k = 10 # For example

with Session(engine) as session:

nearest_artobjects = session.exec(

select(ArtObjects, Embeddings.image)

.order_by(Embeddings.image.cosine_distance(embedding))

.limit(top_k)

.join(ArtObjects)

).all()

return list(nearest_artobjects)

SQLModel is a relatively new package which hasn't fully matured yet. But we figured it was useful for our intents and purposes, since we stick to relatively simple operations. In our case it worked really well to keep our code clean, as the schema validation by pydantic and SQLAlchemy ORM objects are represented by one object.

Text-to-image search 📜 → 🖼️

When a user text query comes in, we simply embed it using the CLIP text model, and find the top-k nearest neighbors using pgvector.

We pass the embeddings through our fitted PCA, which projects the embeddings down to (x, y), which the frontend uses to position the artwork.

Image-to-image search 🖼️ → 🖼️

The user passes us a unique id of an artwork. We use this to find the embedding of that artwork, and the top-k closest artworks. We again use PCA to obtain (x, y) for each artwork, and return all data.

Performance tuning 🚀

When you add a Vector type to a table in Postgres, it doesn't add an index. This needs to be done separately.

We use the HSNW index that pgvector supports as a vector index.

The readme file of the repo explains how to set it up, which we followed.

We increased the maintenance_memory in postgresql.conf, but still couldn't use the full compute that we wanted.

After lots of trial, error, and Googling, we found out, because we were running Postgres in a Docker container, which had a standard limit on the shared memory.

Once we increased shm_size in our docker compose file, the index was created relatively quickly.

We preferred the HSNW over ivvflat, since it can grow along with the data in the database, thus scaling to more artworks that we could potentially add.

Frontend 💻

For the frontend, we have gone for Nuxt with Tailwind for the styling. We both have quite some experience with Vue and Nuxt and it's a pleasure to work with! The ecosystem it's also maturing, so there are quite a few official libraries available that help simplify boilerplate such as dealing with images, fonts and styling.

The main interactive canvas is powered by PixiJS. It renders all the images and animations and is chosen for its speed and ease of use. Since users can spawn quite a few images at the same time we needed it to be powerful and easy to optimize. For the interactive element of the canvas we used pixi-viewport as a viewport to allow scrolling and zooming with both a mouse, keyboard and touchscreen on mobile devices.

Finally, we realized we need to be able to cull images. Culling is a technique where you check which images are currently visible to the user and only render those. So if there are 100 images loaded on the frontend, but the user has zoomed in and can currently only see 20, we simply don't render the remaining 80. This gave us a massive performance boost! In order to do this in PixiJS, we used pixi-cull. The only downside was that the newest version of PixiJS was not supported by pixi-cull so we had to port the culling algorithm ourselves.

Now, when a user submits a query and new artworks come in, we plot them in the pixi canvas, at point:

(x * WORLD_WIDTH, y * WORLD_HEIGTH)

This works, because the backend scales the (x, y) to be within [0, 1], using min max scaling.

The images themself are not stored in our database. Rather we save a URL that points to a high quality version hosted by Google on their CDN. This is also how we did the image scaling discussed earlier. The URLs are provided by the Rijksmuseum API that we scraped.

Deployment 🌐

For deployment, we went with Dokploy, an open-source, self-hostable alternative to platforms like Heroku, Vercel, and Netlify. We set it up on a Hetzner VPS because their servers are cheap and reliable.

Our setup is a monolith hosting the PostgreSQL database, frontend, and backend all in one. If we need to scale, we can either upgrade to a beefier VPS or add more servers and set up Docker Swarm for autoscaling. For now, though, that’s overkill for a hobby project.

Dokploy uses Nixpacks, which made deploying super smooth. It handles backend builds without needing Dockerfiles. Plus, it supports easy to setup zero-downtime deployments with Docker Swarm. Overall, Dokploy + Hetzner turned out to be a simple, affordable, and solid choice for our needs.

Total cost 💰

- Hetzner hosting: €7.62/month (also hosts other projects)

- Runpod serverless GPU: $7.33 ~ €6.95 once (includes all test runs)

- artexplorer.ai domain name on Namecheap: €76.23/year

As you can see, hosting a simple and fun AI application doesn't have to be expensive! Especially if you don't feel the need to buy a fancy .ai domain 😉.

What we learned 🧑 🎓

This project was a huge learning experience for us! While we were already familiar with PostgreSQL, trying out pgvector was completely new. It was exciting to see how easily we could use it as a vector database. Postgres continues to prove itself as a great starting point for almost any project. You can always switch to a fancy use case specific database when your project needs it.

We also dove deep into making Python more performant when handling heavy IO and compute tasks simultaneously. Our current approach combines multiprocessing, multithreading, and asynchronous IO. While it worked well performance-wise, it turned out to be pretty complex. In hindsight, using serverless workers might have been a better option. By passing batches (e.g., list[tuple[id, image_url]]) to individual workers, we could avoid explicit multiprocessing altogether, keeping the code simpler and easier to maintain.

This would probably be worth some extra overhead of starting and stopping the workers.

You made it to the end!

Here is the code, to the artexplorer in case you want to check it out.

Future improvements ✔️

While the project is finished for now, there are a couple of things we like to do in the (near)future:

- Automate the triggering of our ETL pipeline using a tool such as Dagster

- Find publicly available art API's to scrape (The Met in New York seems like a good next candidate)

- Write an API wrapper for the new sources

- Rerun pipeline and embed the new images

- Experiment with other dimension reduction algorithms like umap

- Persist the 2D coordinates from dimension reduction rather than always calculating them on the fly on API calls